NewTestament Introduction is to be distinguished from (1) NT Survey, which givesan overview of the content of the NT; and from (2) Special Introduction to theNT, which looks at such matters as the authorship, date, style, criticalproblems and so forth for each of the individual NT books. We cover the first of these in ourcourse NT Survey, and the material of (2) is distributed through ourcourses Synoptic Gospels, Acts and Pauline Epistles, and Johannine Literatureand General Epistles.

Thiscourse will cover three broad areas relating to the New Testament as a whole,namely (1) the language of the NT; (2) the text of the NT; and (3) the canon ofthe NT. We will cover the firstand third of these rather briefly, but the second (because of its complexity)in more detail.

I. The Language of the New Testament

TheNT was originally written in Koine Greek (with the possible exception of theGospel of Matthew, which matter is discussed in Synoptic Gospels). Koine Greek is the name given to theform of the Greek language which was popular at the time of Jesus' ministrythroughout the eastern part of the Roman Empire.

Beforewe examine this form of the Greek language in more detail, consider its contextamong the other languages of the world and among other forms of Greek atdifferent times in its history.

A.Linguistic context of the Greek Language

Greekis one language in the Indo-European Family. The assignment of languagefamilies is based on similarities of vocabulary and syntax, and is thought toindicate that the languages of a family are descended from a commonancestor. Consider the followingexamples of vocabulary similarity:

Indo-EuropeanLanguages: look at very basicwords

| English German Latin Greek | father Vater pater πατήρ | mother Mutter mater μήτηρ | son Sohn filius υÊός | daughter Tochter filia θυγάτηρ |

Afro-Asiatic Languages: by contrast, look at the same words inthese:

| Hebrew Aramaic Arabic | ab abba abu | em imma um | ben bar iben | bat bara bint |

Linguists have identified a number ofmajor language families, plus many others with far fewer speakers.

1. Major language families:

Indo‑European. Greek and W. European languages

Afro‑Asiatic. W. Asia and N. African (inclSemitic)

Niger‑Congo. Central African

Dravidian. S. Indiansub‑continent

Malayo‑Polynesian. South sea islands & S. Pacific

Sino‑Tibetan. Chinese, related languages

There are others, but they have no clearrelationship to these main families. Language diversity fits pretty well the Babel model ‑ linguistsare not able to explain diversity as common descendents of one language.

Each of these families can be subdividedinto specific languages or, for some of the larger groups, into sub-families:

2. Indo‑European sub‑families:

Germanic => English, Dutch, Scandinavian, German

Celtic => Wales, Scotland, Ireland, some of France (Gaelic, Breton, Scot)

Romance => (having to do with Rome) Latin, Italian, Spanish, French,Rumanian

Greek => Not closely linked to other sub‑families

Slavic => Russian, Polish, Czech, Slovene

Iranian => Old Persian, Modern Iran (some Arabic influence, but Arabic is notI‑E)

Indic => Sanskrit, some of India and others

These subdivisions show us something ofhow early languages diverged, partly within historical periods where we havewritten evidence, partly in times and places where the culture was illiterateor writing has not survived.

Sanskrit and Greek are the oldest Indo‑Europeanlanguages with known extant writing back into the 2nd millenium BC (before 1000BC).

B. Sketch History of Greek Language:

Though language is defined by linguistsas the spoken form of the language, this is not accessible for ancientlanguages, for which all of our evidence is written.

Writing Systems: human languages have used 3 types

1)Ideographic. Symbol represents awhole word. Symbol gives no hintof pronounciation; e.g., Chinese, with typically 1000's of symbols.

2)Syllabic. One symbol for eachsyllable. Directly linked topronounciation; e.g., Babylonian cuneiform, with typically 100's of symbols.

3)Alphabetic. Symbol per component sound;e.g., English, with typically only 10's of symbols.

HISTORYOF GREEK

|‑ 1500 BC

Mycenean‑Minoan |

EARLY |

Homeric |‑ 1000 BC

|

c600 BC ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑ |

CLASSICAL | ‑ 500 BC

c300 BC ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑ |

|

|‑ 0 BC

HELLENISTIC |

|

|‑ 500 AD

c600 AD ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑ |

|

BYZANTINE |‑ 1000 AD

|

|

c1500 AD ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑ | ‑ 1500 AD

|

MODERN |

|‑ 2000 AD

1. EARLYPERIOD ‑ fromearliest known examples of Greek through Greek dark ages (before 600 BC). 2 sub‑periods:

a.Mycenean (about time of Moses). Had writing: Used a syllabary (deciphered in 1950's)

‑Volcano explosion weakened Minoan civ. on Crete

‑Culture dies around 1100 BC with Dorian invasions

‑Knowledge of writing lost [Dark age]

b. Homericperiod (1100 ‑ 600 BC)

‑pickedup alphabet, apparently from Phoenicians

‑writingredeveloped after Dark Ages

2. CLASSICAL PERIOD ‑ 600 to 300 BC

Sonamed because it was the golden age of Greek language and literature.

Startedin W. end of Asia Minor (Ionia), peaked in Athens: oratory, drama, philosophy,history writing.

Severaldialects now show up; probably around before but no written evidence known:

a.Ionic - spoken in W Asia Minor and Greece proper; most important subdialect isAttic, that of Athens

b.Aeolic - spoken in some areas of Asia Minor where first lyric poets were. Became traditional dialect forlyric poetry.

c.Doric - from Dorians (more barbaric Greeks) who invaded about 1100 BC; inAthens, this viewed as "lower class" dialect, used in plays forchorus of bystanders.

3. HELLENISTIC PERIOD ‑ 300 BC to 600 AD

So named from verb"hellenizein," to live like a Greek.

Startswith Alexander the Great spreading Greek into the Middle East when he conquersall that area.

Greekdialects first mixed among army members from different regions and cities.These men then settled in various Middle Eastern cities.

Greekbecomes the second language for many locals, so dialects mixed andsimplified from the styles used by playwrights. Second-language people tend to use simpler syntax andfamiliar parallels from their native language.

TheRomans left Greek intact when they conquered the east. Greek was finally pushed back by Muslimand Barbarian invasions of Persia, Africa and Asia Minor, and Arabic became thedominant language in much of this area.

The term"Koine" (Gk for "common") is used for this dominant Greekdialect used in the Hellenistic period.

Writersof the period often imitated the classical Greek style (somewhat as we pray inKJV English). Neither we nor theydid very well from a linguistic perspective!

N.T.Greek is one variety of the Koine Hellenistic Greek. It was influenced by Hebrew via the Septuagint translationof the OT and by the second language problem.

4. BYZANTINE PERIOD ‑ 600 to 1500 AD

Namedfor the Byzantine Empire and its capital Byzantium (Constantinople).

Greekis pushed back with Byzantine Empire except for isolated pockets(monasteries, etc.).

Constantinoplefalls in 1453 AD.

5. MODERN PERIOD ‑ 1500 to present

In 1830's, Greeks were freed from the Turks.

C. Changes in Greek over its history.

1. Changes from Classical to Koine Greek.

Thelanguage tends to simplify as we go from Classical to Hellenistic dialects:

a.Dual number disappears.

Originallyhad singular, dual, and plural endings for both nouns and verbs.

e.g.,τω Îφθαλμω

Dualwas used for "pairs" (eyes, arms, etc.)

Wasnot common in Classical, is never seen in Koine.

b.Optative mood much decreased use.

Usedin NT mainly in stereotyped phrase:

μ¬γέvoιτo - "May it never be!"

AlsoI & II Peter, Jude: "Be multiplied" used in greetings:πληθυvθείη

Occursonly 67 times in NT, mostly Paul's "May it never be!"

c.Fewer μι verbs.

μιverbs have a different set of endings from ω verbs, so more forms tolearn.

Whenlearning a second language, tend to choose the familiar, more common ωverbs.

d.More compound verbs.

Addingprepositions to verbs multiplies vocabulary easily, e.g., ¦ξ-,εÆσ-,κατέρχoμαι for go out, in, down.

[contrastHebrew verbs hlk, ytsa, boa, yrd;go, -out, -in, -down]

Compoundverbs not so common in earlier Greek, but when it became a popular 2nd languagethis simpler route was taken.

e.Simpler Syntax.

Thismay be an artifact of the surviving literary works:

dramaand history for Classical vs.

privateletters and receipts for Koine.

Spokenclassical Greek might not have had the difficult syntax (less info on whatspoken Classical was like), but the classical literature did.

2. Changes from Hellenistic (NT) toModern Greek.

a.Disappearance of Dative.

Replacedby preposition plus accusative (like English "to" w/ accusative).

b.Disappearance of Infinitive.

Replacedwith participle (a verbal adjective used substantively as a noun).

c.Increasing use of Helping Verbs and Verbal Particles.

AncientGreek added augments and endings to verbs.

ModernEnglish uses helping verbs: "He has walked."

ModernGreek for continuous action uses εÆμαι "to be".

" " for perfect tense uses §χω "to have".

" " for future tense uses particleθα plus the present tense.

" " for subjunctive mood uses particle vα plus thepresent tense.

d.Some inflectional changes.

Someverb endings have changed. e.g., Present Active Indicative: -ω, -εις,-ει, -oμε(v), -ετε, -oυv

e.Simpler Syntax.

Allmoved in the direction of simpler style.

Notsure why, as in modern times there are fewer speakers of Greek.

PerhapsTurkish control meant that there were few who were well educated, so languageis simplified by "rural" non‑literary use (same thing happenedto English between William the Conquerer and Chaucer).

Inmodern Greek there are two written "dialects":

1)Puristic (more Classical, formal use),

2)Spoken (more colloquial, used on the street).

D. Influences on N.T. Greek.

How does NTGreek differ from the Koine Greek of the time?

Theyare very similar, but some slightly different influences.

1.The Greek of the NT was that being spoken at the time.

NTwritten to communicate to the man on the street.

Fewexamples of "classicizing" in NT: sections like the intro. of Lukeare probably in the literary Greek of the time.

2. Classicalbackground.

Althoughno one was speaking Classical Greek, it was still being read and heard in play performances, etc.

LikeOld English influence into 20th century through Shakespeare and KJV.

3. Semiticbackground.

a.Most of the NT writers are Jewish in background (Luke is surely a Gentile).

EitherHebrew or Aramaic is their native language, or the Greek they spoke was aJewish Greek.

Lukeis traditionally Syrian => some Semitic influence.

b.Even Luke would read the OT Scriptures in the Hebraistic Greek of theSeptuagint.

Structuredifferences: Somewhat Hebraistic syntax

Vocabularydifferences: Words used in LXX slowly picked up a spiritual rather than a paganmeaning (from Septuagint usage for about 3 centuries).

Grammarand meanings of Greek words in NT were often influenced by the Septuagint.

E. Application of this language historyto N.T. exegesis.

N.T.Greek differs grammatically and lexically from both Classic and Moderndialects:

Manywords have different meanings,

Afew similiar problems with grammatical forms

Sowe need to study Koine Greek plus Hebrew.

Tounderstand N.T. Greek, we need as a helpful background:

ClassicalGreek

Papyri(Hellenistic)

Septuagint

Modern Greek(some)

Hebrew

Thankfully,most of this work is done for us by the available lexicons and grammars,if we will consult them.

1. Lexical Matters.

Having todo with word meanings, compare "lexicon," meaning dictionary, moreremotely "lecture."

a. ReferenceLexicons.

1)Classical Greek.

Liddelland Scott: 3 different sized eds., big, middle and little.

Iftranslating from Septuagint need largest ed.

2)Papyri. Not much studied beforeabout 1900.

Moulton& Milligan, Vocab. of Gk. Testament

M& M updated Thayer, but not easy to use.

Thankfully,it information was incorporated into BAGD, below.

3)Septuagint. No separate Lexicon(use Liddell)

Theologicallexicons (below) helpful.

4)Theological Lexicons [Dictionaries of NT Theology]

Lookat words that have theological significance

Kittel/Bromiley,Theol Dict NT 10 vol.(liberalish).

ColinBrown, New Intl Dict NT Theol3 vol. (better).

Bothsets suffer from problem of tending to transfer whole range of word'smeaning into each particular context (called “illegitime totality transfer”).

5)Best All Around Lexicon for NT.

Bauer,Arndt, Gingrich, and Danker, Gk-Engl Lex of NT and Other Early Xn Lit

BAGDincludes words for early church fathers also.

Extensivebibliography for discussions of word meanings and occurrences of words outsideNT.

6)New Dictionary putting synonyms, etc., together.

Louwand Nida, Gk-Engl Lex Based on Semantic Domains

Veryhelpful discussion of ranges of meaning and of uncertainties regarding nuances.

b.Example of etymology and change of meaning through usage:

Considernoun ¦κκλησία,usually translated "church."

Etymologically,from ¦κ + καλέω =call out (from).

Butusage, not etymology, determines meaning.

E.g.,in English, word "church" means (1) building, (2) denomination, (3) localcongregation, (4) universal church.

InNT Greek, ¦κκλησίαdoes not mean (1) or (2) above.

1)In Classical Greek, ¦κκλησίαmeant "a meeting," usually a particular type, "a calledmeeting."

Wasused for governmental assemblies or informal gatherings to decide something(cf. Homer, Herodotus, Josephus).

NThas an example of this secular usage:

Acts19:39 and 41 ‑ the riot in Ephesus

v.39"it should be settled in a lawful assembly."

v.41refering to this irregular assembly.

2)In Septuagint (made around 250 BC), ¦κκλησίαoccurs over 75 times, and is often a translation of qhl meaning "all the people gathered atone time."

Usedfor the gathering of all Israel for festivals and/or to hear God's word (not agovernmental assembly).

Appliedto the assembly of Israel in the wilderness.

NThas example of this too; Stephen in Acts 7:38).

Someeschatological meaning also, when all gather before God at the end.

Sothe word has picked up a religious meaning by NT times.

3)In NT usage, we see a blending:

Wordretains "assembly" and "local" idea from Classical Greek.

Wordretains "religious assembly" and "universal" idea fromSeptuagint.

Addsa new specific idea: a collective term for those who accept Christ as Savior.

Pauloften adds a phrase to the word (e.g., "Church of Jesus Christ") toindicate this non‑pagan and non‑Septuagint usage.

Sothe word has some changes and some continuity.

Therefore,must determine word meanings from usage and context.

cp.English word "manufacture":

etymologically(from Latin) means "make by hand"

butcurrent usage is exactly the opposite!

2. Grammatical Matters (having to do withsyntax).

a. Grammars

Allgrammars today have tried to assimilate the results for NT from ClassicalGreek, LXX, Papyri, etc.

Machen,NT Gk for Beginners,is a beginning Grammar; so is Mounce, Basics of Biblical Greek, which we plan to begin using.

Brooksand Winberry, Syntax of NT Greek,is intermediate level (as is Zerwick).

Advanced grammars:

A.T. Robertson (prob best for seminary students, pastors).

Blass,DeBrunner, and Funk (more recent and technical, but smaller, harder touse).

Moulton,Howard, and Turner (multi-volume; expensive but good).

b. An Exampleof Hebraism in NT Greek.

Considerthe use of "εÆ" in Heb 3:11, a quotation from Ps95:11:

Ps. 95:11 Heb. 3:11

.! im εÆ

0&!"* yavoün εÆσελεύσovται

--! el εÆς

*<(&1/ manuhoti τ¬vκατάπαυσιv μoυ

Twopossiblities:

LiteralGk: "If they will enter into my rest"

Hebraism:"They will not enter into my rest"

Turnson word translated "if"

.! ‑ also used to mark a strongnegative in an oath.

εÆ‑ only 'if,' never a negative in "gentile" Greek.

Somethink that this is a mis‑translation. I think this is a Hebraism carried over into Greek via aHebraistic dialect.

Anotherexample of same construction (with no LXX background) is found in Mark8:12:

εÆ δoθήσεταιτ± γεvε’ταύτ®σημεÃov.

"Thisgeneration will not be given a sign."

εÆis clearly used as a negative here in context.

II. The Text of the New Testament.

A real concern throughout church historyhas been the text of the NT. Heretics have regularly tried to add additional books to canon (we willdiscuss canon under III). Occasionally they have tampered with its text (Marcion and some modernliberals). Atheists and Muslims(and sometimes Mormons) have argued the text is unreliable. Some Fundamental Christians have pushedstrongly for KJV only.

Here we will consider the text of the NewTestament under three topics:

(1)sources of the text,

(2)history of the text, and

(3)the practice of text criticism.

A. Sources of the Text.

1. Modern printed editions of the GreekNT.

We start here,rather than with the ancient manuscripts, as this is what we personally haveaccess to.

a. Greek Textscurrently (or recently) in print.

1)Most recent editions:

a)Modern Critical Editions: (Madefrom scratch using manuscripts of Alexandrian family as most reliable).

Nestle‑Aland,Novum Testamentum Graece,27th ed., (1994). Significantchanges between eds. 1-25 and 26-27.

UnitedBible Society, Greek NT,4rd ed., (1993). Big changes invariants displayed since 3rd ed.

Bothhave identical texts (as planned) but format and method of noting textual variationsdiffers.

b)Majority Text Edition:

Hodges/Farstad,Gk NT acc to Majority Text(1982). Prints text having largest number of manuscripts in support(Byzantine family), lists alternatives in footnotes.

2)Older editions, based mostly on 19th century work (Alexandrian emphasis).

EarlierNestle‑Aland editions (1‑25).

Textwas chosen by very mechanical method:

Usedmajority vote of texts by:

Westcottand Hort,

Tischendorf8th ed,

BernardWeiss.

If2 or more of these texts agreed, then that is what was printed.

Britishand Foreign Bible Society.

Took5th Nestle ed, used more readable Greek type and English (rather than Latin)notes.

Souter'sGreek NT (1905).

Somewhatcloser to Byzantine than N-A editions.

SeveralRoman Catholic eds: Vogels, Bover,Merk.

3)Pre‑19th century editions (Byzantine emphasis).

Severalforms of the Textus Receptus are still being printed today; e.g.:

TrinitarianBible Society (1976).

FollowsTheodore Beza (1598 ed); modified to match KJV where KJV followed other Greekmanuscripts instead of Beza.

b. TextualApparatus of UBS and Nestle.

1) UBS Apparatus applies to 4th ed.only.

Type:pretty clear (UBS started a new trend in clarity, but 4th ed. not as nice as1-3).

Quotationsfrom OT: bold type.

Section‑headings:English.

Brackets:Probably not original reading, but

important enough to note.

Footnotes:

Bottom(small print): Cross references toOT and NT texts which are quoted or similar.

Middle(small): Discourse segmentationvariations in printed texts and major modern language translations.

Top(large print): Textual variants.

TextualVariants:

UBSdoes not include as many places of variation as Nestle, but UBS gives moreextensive info on each. Onlyprovides variants which committee felt might make a difference intranslation. Committee for 4th ed.made numerous changes on which passages to cite variants for.

Orderof variants listed is typically best to worst.

Orderof support cited: papyri, uncials (code: numbers which start with zero),miniscules, ancient translations, quotes from church fathers (names spelledout).

Variantusually given in original Greek; sometimes in English where variant notpreserved in Greek (e.g., Latin, Coptic).

Certaintyof the text (according to the committee) is shown in brackets { }:

A= text is certain;

B= almost certain;

C= Committee had trouble deciding;

D= Comm had great difficulty.

ASSIGNMENT: Read introductory material of UBS GkNT. For mid-term test; will give asample of a variation and ask if papyri, uncials, etc. support each alternative,etc., and what various other abbreviations mean.

2)Nestle's 26th edition.

Type:much improved over eds. 1-25, but not quite as nice as UBS (smaller size type).

OTquotations: italics instead of bold.

Nosection‑headings.

Brackets:same as UBS.

Variantsin text: Superscript symbolsindicate kind of variant

This code also used inall earlier editions:

┌ = variant at this word.

┌ ┐ = variant at these words.

┬ = something inserted in othermanuscript(s).

" = some texts omit this word.

Q\ = some texts omit these words.

s = change of word order.

s s =change of word order between symbols.

: = different punctuation.

Outermargins: Cross‑reference to OT and NT parallels. Much more extensive than UBS."!" marks very important parallels.

Innermargins: Ancient divisions of text, intermediate in size between modernchapters and verses; Symbols of Eusebius: made it easy to find parallelpassages in Gospels.

Footnotes:Textual variants.

TextualVariants:

Verycompressed cp to UBS.

Notesmany more variants than UBS (perhaps 5x as many), all known variants except fortrivial spellings.

Veryabbreviated, harder to figure out which texts support which variants. 26th ed. improved over earliereditions.

Notmuch on church fathers.

2. Ancient Greek Manuscripts.

These are copies (complete or damaged)made by hand (before the invention of printing or shortly thereafter) of partor all of the NT in the Greek language. They are traditionally subdivided by the type of material on which theyare written and the type of handwriting used into three groups:

(1)papyri,

(2)uncials, and

(3)miniscules.

a. Papyri(plural; singular is papyrus).

Name givento manuscripts written on a type of "paper" made from a suitable typeof reed. (More on this under"book production" later).

Particularpapyrus mss of the NT are abbreviated by a p followed by a superscript number.

As of1981, we have 86 different manuscripts of papyri. 88 catalog numbers were used,but some of these were later discovered to be parts of another ms.

Papyrionce listed in order of age p1, p2 ..., but many more found after firstcatalogued; renumbering would produce incredible confusion.

Mostup-to-date information on manuscripts is in Aland and Aland, The Text of theNT (Eerdmans, 1987).

1)p52 is the oldest. Called "John Rylands Papyrus."

Smallfragment of Gospel of John, chapter 18, about the size of a silver dollar.

Writtenon both sides, implying bound in book style rather than as scroll.

Datedearly 2nd century (100‑135 AD). Dating of mss is somewhat fuzzy as based on handwriting style. Not till medieval period do manuscriptshave dates put on by scribes.

Locatedat John Rylands Library, Univ of Manchester, England.

2)A group of papyri from about 200 AD:

p32‑ Fragment of Titus.

Justa few verses

Alsoat John Rylands Library

p46- Chester Beatty papyrus of Pauline Epistles.

Largeand therefore important.

ContainsPauline epistles, incl Hebrews

InChester Beatty Library in Dublin, Ireland.

p64,67‑ Now recognized as from the same manuscript.

Fragmentsof Gospel of Matthew.

AtBarcelona and at Magdalen College, Oxford

p66‑ Most of Gospel of John.

InBodmer papyri collection in Switzerland,

plusfragments at Chester Beatty Lib, Dublin

p77‑ Fragments of Matthew (perhaps as early as 175 AD). One of theOxyrhynchus papyri, at Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

3)Early 3rd century:

p23‑ Fragments of James, chapter 1.

AtUniversity of Illinois

p45- Chester Beatty Gospels & Acts.

Originallycontained all 4 Gospels and Acts, now very fragmented.

p75‑ Bodmer Luke and John.

TwoGospels in one volume.

4)Distribution of Known Papyri (85 as of August 1980):

Century | Number

________ |___________________________

|

1 | 0(Possibly Mark at Qumran)

2 |* 1

3 |******************************* 31

4 |******************** 20

Later |********************************* 33

|

No papyrihave survived virtually complete; all are fragmented. Their value is rather in their early date than in theircomplete text.

No papyriof whole NT; weakness of papyrus did not allow binding all in one volume. Typically bound as 1 or 2 Gospels;Paul's letters; Acts and/or Catholic Epistles; Revelation (when in multivolumesets).

b. Uncials.

This is not a very good name("uncial" is term for hand‑written capital letters), sincepapyri are written in uncial handwriting also. Name was chosen before papyri were discovered.

Uncial manuscripts were written onparchment, a type of "paper" made from animal skins. Very expensive but also very durable.

Uncials are abbreviated by capital Latin(English) letters. After these ranout, the different-looking Greek letters were used. Then used numbers that always start with '0' (zero; todifferentiate from miniscules, which are marked by numbers without leadingzero).

1)3rd century.

0212- Dura Diatessaron ‑ Harmonyof the 4 Gospels. Must datebefore 256 AD as found under the wall foundation of city (Dura) destroyed in256. At Yale University.

O220‑ Romans (fragment).

0171- Gospel (frags of Matt, Luke), about 300 AD.

O162‑ John (fragment), 3rd or 4th cen.

0189- Acts (fragment), 3rd or 4th.

2)4th century.

! (01) ‑ Codex Sinaiticus.

Discoveredin St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai (built c600 AD).

Possone of the mss drawn up at Constantine's request (4th century), later brought to monastery.

Containsthe complete NT & OT (but parts of OT lost in damage to ms)

Nowin British Museum, London.

In1850's Tischendorf got the Monastery to donate manuscript to the Czar ofRussia.

Communistssold to British Museum in 1933.

Somemore frags found recently at St. Cath. Monastery.

B(03) ‑ Codex Vaticanius. InVatican library.

Earlyhistory unknown, first Vatican catalog in 1475 listed it.

ContainsOT, Apocrypha, and NT (end missing).

Booksare in different order than our Bible.

MissingHeb 9:15‑, 1‑2 Tim., Titus, Phm. and Rev.

Severalfragments also from this century.

3)Later (5th century).

A(02) ‑ Codex Alexandrinus.

WholeNT, missing some of Matt. & 2 Cor.

Knownearliest in Alexandria.

Patriarchof Constantinople had it, was friendly to west, so in 1627 he donated it toCharles I of England.

Nowin British Museum.

C(04) ‑ Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus.

About5/8 of NT.

Sermonsof Ephraim are written over NT text.

Nowin Paris National library.

D(05) ‑ Codex Bezae.

Containsthe Gospels and Acts.

HasGreek and Latin on facing pages.

Nowin Cambridge U. Lib., gift of Theodore Beza.

Locationand history prior to Beza unknown.

W(032) ‑ Codex Washingtonensis.

Completemanuscript of the Gospels.

Foundafter 1900 in Egypt. Purchased by Freer in 1905.

Donatedto Smithsonian (now in Freer Gallery of Art).

5)Distribution of Known Uncials (245 in Aug 1980).

Century | Number

_________ |______________________________________________

|

1 | 0

2 | 0

3 |*** 3

4 |**************** 16

5 |******************************************** 44

Later |********************************/ /*** 182

Uncialtype of handwriting continues until 11th cen., but begins to be replaced byminiscules in 9th.

c. Miniscules.

Name "miniscule" refers to thesmaller cursive handwriting style in which these manuscripts written. Forapproximate comparison, uncials look like our printed Gk capitals, minisculeslike our printed Gk small letters.

Miniscules span 9th to 16th century untilprinting starts. Most are writtenon parchment, except for a few on paper towards the end of this period.

Asof 1980, 2650 miniscules known.

Miniscules areabbreviated/labelled by normal numbers: 1, 85, etc.

Miniscules are generally considered oflesser value for determining the NT texts, as they are much further removed intime from the originals:

Papyriremoved 40-700 years,

Uncialsremoved 200-900 years,

Miniscules800-1800 years.

However, some miniscules are probablyjust one or two copies removed from important uncials which no longer exist.

1)Important Miniscules:

Group1: contains miniscule number 1

Calledthe "Lake group" after the man who studied them.

Probablyall have common ancestor.

Includesmss 1, 118, 131, etc.

HaveCaesarian type text.

Group13: contains ms 13

Calledthe "Ferrar group."

Includesmss 13, 69, 124, etc.

AlsoCaesarian family.

Miniscule33

9thcen., one of earliest miniscules.

Apparentlya copy of an early uncial.

Oncecalled "Queen of the cursives"

GoodAlexandrian family text.

2)Distribution of Known Miniscules (2650 as of Aug 1980)

Century | Number (+ represents 10 mss)

_________ |______________________________________________

|

9 |+ 13

10 |++++++++++++ 125

11 |+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 436

12 |++++++++++++++++/ /+++ 586

13 |++++++++++++++++/ /+ 569

Later |++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++/ /+++ 921

d.Summary: Papyri, Uncials,Miniscules.

Bestsources of NT text.

Fragmentarybefore 4th century.

Giveno direct information on their date, copier, where copied, from whatmanuscript(s), except for a few medieval mss. This information can sometimes bededuced.

3. Other Ancient Sources.

a.Lectionaries (Greek).

Could have put these under previousheading "Ancient Greek Manuscripts," as they are old, Greek and handwritten,but lectionaries have reorganized the text for reading in church on particularSundays. Some lectionariesare based on the calendar year, some on the movable church year (3rd Sun ofLent, etc.).

Early church practice was just to have alist to look up text in Bible. Later, readings were compiled into separate books called lectionaries.

Wehave lectionaries from the 4th century on.

As of 1980, 1995 lectionaries known:

271uncial lects (4th-13th cen),

1724miniscule lects (9th-16th cen).

UBS will sometimes list them infootnotes, either as a whole ('Lect' = Reading of the majority of lectionaries)or individually l76,150

Nestledoes not usually note lectionary readings, giving only five lect mss in theirmss list.

Lectionaries have not been studied asthoroughly as papyri, miniscules and uncials, but they appear to have littlevalue for the original text or its early history.

b. Versions(i.e., Ancient Translations)

The NT has now been translated into manyhundreds of languages. Several ofthese translations were made before the fall of the Roman Empire (475) or atleast before the rise of Islam (650). We list these ancient translations below:

Century: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Latin: Old Vulgate

Syriac: Old Peshitta

Palestinan

Harclean

Coptic: Sahidic

Bohairic

Century: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Other: Gothic

Armenian

Georgian

Ethiopic

Nubian

WhenChristians first spread the Gospel, it was in two languages: Greek and Aramaic (for Jews). Most agree that the NT was written inGreek, except possibly for Matthew.

Need forAramaic disappeared after Jews largely rejected Christianity (70‑150AD), and Messianic Jews died off. Some argument on connection of Syriac with Aramaic.

Asthe Gospel spread, it encountered people who did not know Greek.

1)Latin Versions of NT.

a)Old Latin (probably 2nd century).

Wasin existence by the time of Tertullian.

Firstmade in Europe or Africa (not Rome, too many people there knew Greek).

Don'tknow who did it; There is much variation, possibly several versions,or people correcting one translation.

CalledItala, abbrev. in UBS and Nestle as 'it.'

By4th century there were so many variations that bishop of Rome called for anew translation.

b)Vulgate (late 4th and early 5th century).

Thatnew translation was Jerome's vulgate, not strictly a new translation but arevision of the Old Latin (Western family) in light of the bestmanuscripts available at the time (Alexandrian).

Manyold readings crept in as it was later copied, since people were still familiarwith the Itala.

Wasblasted at first (as was KJV!), but gradually accepted as the standard.

Bythe Reformation, people were correcting the Gk and Heb texts by theVulgate (supposedly inspired!).

UBSand Nestle abbreviate as 'vg'.

2)Syriac Versions.

Syriac was a dialect of Aramaicspoken by Gentiles in Syria. The main difference between Jewish Aram. and Syr. is handwritingstyle (same alphabet but very different script).

Syriac versions have apparently picked upsome influence from the Diatessaron, which was early in Syriac, perhapsbefore the four Gospels.

a)Old Syriac version (by 2nd or 3rd century).

Onlytwo manuscripts survive, contain the Gospels.

Textof two mss are significantly different.

Sinaitic(syrs in UBS, Nestle sys) 4th ‑ 5th cen.

Curetonian(syrc in UBS, Nestle syc) 5th cen.

b)Peshitta (syrp in UBS, Nestle syp).

Namemeans 'simple', sometimes called the "Syriac Vulgate," is thecommon Syriac version.

Wasmade around or before 400 AD (late 4th, early 5th), because in 431 AD theSyriac church split into two factions, and both use the Peshitta. Tradition connects it with Rabbula, bpof Edessa (411-435).

Stillused in the Syriac church today.

Mostthink that Syr was translated from the Greek, tho Lamsa thinks Syr is original.

OtherSyriac versions:

c)Palestinian (syrpal in UBS, Nestle doesn't cite).

A6th century revision of the Peshitta.

d)Harclean (syrh in UBS, Nestle syh)

A7th century revision of the Peshitta.

3)Coptic Versions.

Copticis the name of the Egyptian language at NT times.

Writingstyle had changed with coming of Greeks to Egypt. Got rid of ideograms and syllabary of Hieroglyphic &Demotic, replacing with Greek alphabet (plus a couple of new letters).

Themajor No. Egyptian cities spoke Greek, but as Xianity spread up the Nile, Copticversions were needed.

HaveNT in several dialects but two important ones were:

a)Sahidic (copsa in UBS, Nestle sa).

Thebesand south (Upper Egypt).

Madein 3rd or 4th century.

Stillused by Coptic church today.

b)Bohairic (copbo in UBS, Nestle bo).

Deltaand north (Lower Egypt).

Madein 4th century.

4)Other Ancient Versions.

Other language groups with which Xianitycame in contact after it had become legal and established.

a)Gothic (goth in UBS, Nestle got).

Indo‑European language spoken by Goths (sort ofGermanic). No groups speak thistoday.

Madein the 4th century.

b)Armenian (arm in UBS, Nestle doesn't use).

Eastern part of Turkey, Soviet Union, N. part of Iran andIraq.

Made in 4th or 5th century, still used in Armenian churchestoday (scattered around world).

c)Georgian (geo in UBS and Nestle).

Areanorth of the Black Sea (home of Stalin).

Madein the 5th century.

d)Ethiopic (eth in UBS, Nestle aeth).

Not the same area as today. Was a bit further north (just south of Egypt).

Madein 6th century.

e)Nubian (nub in UBS, Nestle doesn't use).

Areaaround Nile in southern part of Egypt.

Madein 6th century.

These are all of the versions up to timeof Muslim conquest (early 7th century). Once Rome fell (400's) there were few more Western versions until theReformation.

We have more manuscripts of Latinversions (>8000) than of the Greek. Also several thousand Armenian manuscripts.

Whatis the value of these versions?

Someversions were made about as early as the earliest surviving manuscripts whichwe have of the NT.

Thismeans they may help us get closer to the originals.

Themost valuble early versions are:

OldLatin Old Syriac

Sahidic Bohairic

sincethey predate the 4th century (when we start to get reasonably complete Greekmanuscripts).

Notas good as the Gk. manuscripts for determining the best text for two reasons:

1.Translation tends to obscure some details.

Evenbest translations do not show everything (e.g., Latin does not have a definitearticle, but can give good help on verb tenses or on the existence ofa phrase).

Thesewere not the best translations. Not done by linguists, etc.

2.The versions themselves have errors from copying.

Eachversion has its own unique collection of copyists' errors to decipher.

Cansometimes tell if the copy error was in the Gk or the Latin by the translation.

e.g.,Rev 22:19 libro/ligno

vsβιβλίoυ/ξύλoυ

The versions do tell us what kind ofreadings existed at the place where the translation was made, given the abovequalifications.

Can get some locality and dateinformation from versions, knowing where the particular language was spoken,when version made. This helps withdate and localities for Greek manuscripts, which otherwise have no such info.

c. ChurchFathers.

Another important source for study of thetext of the NT is its quotation in early writings. We call these writers the "church fathers" sincemost of them were leaders or teachers in the church. Some, however, were not orthodox, e.g., Marcion.

Thesewritings include letters, sermons, polemics: anything in which a NT quotationappears.

Thismaterial helpful because we usually know their locality and time of writingmore accurately than for versions or Greek manuscripts.

Belowwe give a list and three maps showing the time and place of the major churchfathers.

Church Fathers Significant for TextStudies:

Name Language Location Comment

‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑SECOND CENTURY ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑

Justin Greek [140 AD] Ephesus

Marcion Greek [150 AD] Rome Gnostic

Irenaeus Greek [180 AD] Lyon, Histeacher studied under Apostle John

France

Tatian Syriac [180 AD] Syria Diatessaron

Clement Greek [200- AD] Alexandria,

Egypt

‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑THIRD CENTURY ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑

Tertullian Latin [200+ AD] Carthage,N. Africa

Hippolytus Greek [225 AD] Rome First'anti‑pope'

Origen Greek [225 AD] Alexandria, Egypt

Cyprian Latin [250 AD] Carthage, N. Africa

‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑FOURTH CENTURY ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑

Xianity now legal: Biggest century in Scriptural study sinceapostles and until Reformation.

Ephraem Syriac Syria

Hilary Latin Poitiers,France

Ambrose Latin Milan,N. Italy

Augustine Latin Hippo(near Carthage)

Jerome Latin Bethlehem,Palestine

Chrysostom Greek Constantinople

Gregory Greek Cappadocia,Asia Minor

of Nyssa

Basil Greek Cappadocia,Asia Minor

Gregory Greek Cappadocia,Asia Minor

Nazianzus

Eusebius Greek Caesarea,Palestine Ch History

Athanasius Greek Alexandria,Egypt

SOURCESOF THE NEW TESTAMENT TEXT

LOCATIONOF CHURCH FATHERS BY CENTURIES

KEY:

Diagrams are sketch maps of Mediterranean

Typestyle for name indicates languagefather used:

Greek,LATIN, Syriac

SECOND CENTURY:

Irenaeus

___________ __ / __________

/ \ \ \ / |Justin

__/ Marcion \ \ \ / |_________

/_/\\ \__\ | Tatian

______________ |

| __________|

|______________| Clement

THIRD CENTURY:

___________ __ / __________

/ \ \ \ / |

__/ Hippolytus\ \ \ / |_________

/_/\\ \_ \ |

______________ |

CYPRIAN| __________|

TERTULLIAN |______________| Origen

FOURTH CENTURY:

HILARY

AMBROSE Chrysostom

___________ __ / __________

/ \ \ \ / | Basil, Gregories

__/ \ \ \ / | _________ Ephraem

/_/\ \ \_ \ |

______________ | Eusebius

AUGUSTINE | __________|JEROME

|______________| Athanasius

Whatis the advantage for NT text for knowing the church fathers?

Havebetter information for their locations and dates than we do for versions ormanuscripts. (We generally knowtheir dates of death and where they were active.)

Theircitations of Scripture or comments on variant readings tell us the date andlocation of these readings.

BUTchurch fathers are not the best source for determining the Greek text ofthe NT.

Why? Several problems using church fathers:

1.We must do textual criticism on the text of writings of church fathers to getoriginal Scripture reading.

Thiscan be difficult as scribes have often corrected the father's Scripturequotations to agree with the Scripture texts which the scribe was used to.

2.We do not always know what the father was doing:

Washe quoting from memory, or did he look it up?

Washe making an exact citation or only an allusion?

Ifit is from memory, slight rewordings or combinations of parallel accountsmay have occurred.

Evenlong passages still do not prove that he copied, as memorizing more commonbefore invention of printing.

3.Ephraem, Hilary and others were not writing in Greek and we do not know whatkind of NT manuscript they may have been using (Greek, Latin, Syriac?).

B. History of the Text.

1. Before Printing.

|

2 |

a. Palaeography

Studyof ancient writing styles and techniques

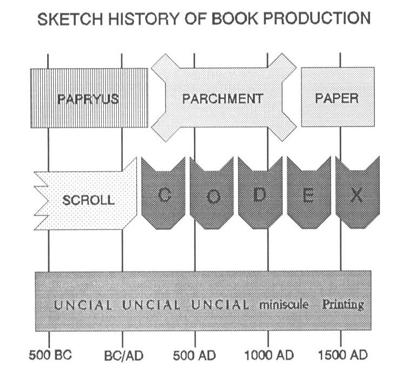

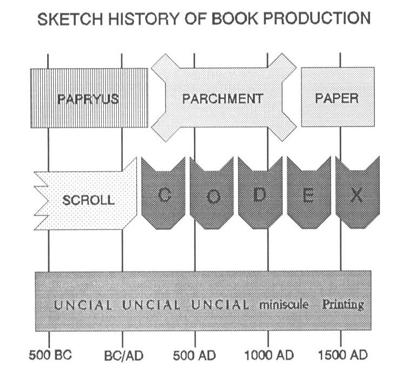

1) Materialsfor receiving writing.

Three main types: papyrus, parchment, paper

a) Papyrus.

Dominantwriting material in the Roman Empire.

Usedfrom before 2500 BC in Egypt up to c300 AD.

Popularworks continued on in papyrus but reference works like the Bible (whichwere used daily) were thereafter made on parchment, as more durable.

Production of papyrus:

Papyrusreed is sliced vertically into thin strips, laid crosswise (#), thenpressed together. Its sap (thinnedwith Nile water) was the glue.

Reedgrew naturally in Egypt and a few other marshy places.

Papyrus"paper" kept fairly well, better than most grades of modern paper, particularly modernacid paper (100's of years possible if conditions right).

Bytoday, however, most have disintegrated.

Insome very dry areas (Egyptian deserts) fragments of papyri are found.

b) Parchment.

Usedfor the Bible from 300 to around 1300 AD.

Speciallytreated animal skins

Production:made suitable for writing by being scraped thin, treated with lime, etc.

Namedfor city Pergamum which was an early major producer. Story has it that king of Pergamum and EgyptianKing Ptolemy were in competition for the biggest library. Ptolemyembargoed Pergamum's papyrus so they developed this instead.

Muchsuperior to Papyrus in durability but harder to write on as it was not asporous (letters could be rubbed off rather easily).

Wasmore expensive and difficult to prepare, but the supply was not geographicallylimited.

c) Paper.

Similarto papyrus in that it is a sheet of vegetable fibers, but fibers weretaken apart and reassembled for paper.

Production:took cloth or wood fibers and cooked them down, then glued together with glueor starch.

Inventedby Chinese who used it by 2nd cen AD.

Muslimconquests of the East brought paper to Middle East about 750. Sold in Europe by 1100s

Crusadersmay have brought back production secrets.

Finallybegan to be used in Europe in 14th ‑ 15th c.

Itsdevelopment was aided by printing, as both were cheaper than competingprocesses.

2) Writingequipment used in antiquity.

a) Pens.

Reed pen:for papyrus; used something like our felt‑tip pens: Took a piece of reed,mushed up the end to form a tiny brush and dipped this in the ink (everyletter or two).

Quillpen: for parchment; used points like our fountain pens have. These hard points would dig holes inthe softer papyrus. The sharp pen points for parchment were featherquills (from chicken, duck, goose, etc.) sharpened at the tip. These were slit to hold a small amountof ink (dip every few letters).

b) Inks.

Black:was made from lamp black (carbon soot) mixed with gum arabic and water. This was the most common ink in NT times.

Brown:was obtained from the galls from certain nut trees. Codex B (Vaticanus) and D (Bezae) were written with thisink.

OtherColors: for deluxe editions, various ink colors like red, purple, gold, andsilver could be made.

c) Pen knife.

Usedto sharpen or to make new quill pens.

d) Pumice.

Avolcanic stone with texture like sandpaper. Used to smooth out writing surfaceand to fine-tune the pen sharpening.

e) Sponge.

Usedfor erasing paper and for cleaning pen point.

3) Book forms.

Howwere books constructed? Two ways:scroll, codex

a) Scroll.

Onecontinuous horizontal roll, of sheets glued or sewn together edge to edge. Thiswas the standard book technique until c100 AD. Use continued long after for pagan literature, but not forNT.

Problemswith the scroll format:

Thescroll cannot be very long as it becomes hard to handle; 20 feet is about thelongest, c40 pages. Usual lengthswere on the order of 10 to 20 feet. Thus most books were short and longer writings were made on many scrolls,sometimes 100 for one work!

Randomaccess problem: cannot find the passage you want without a lot of work (like cassettetapes, video tapes).

Wastedwriting material: cannot conveniently write on the back side as it is handledon that side (so too much wear on a written side).

b) Codex[plural, codices].

Sheetsare linked together along only one edge (like 3-ring binders) instead of bothedges (like scroll).

Ideaprobably came from wax‑coated wooden sheets bound with rings in thismanner, then adapted for papyrus.

Ouroldest NT manuscript fragments are codices (only 4 of our 85 cataloged papyriare scrolls).

Mostscholars guess that the earliest NT manuscripts were written on scrolls, butthe scrolls that survive are not the earliest mss.

c) Palimpsest.

Nota different book form, but a manuscript which has been erased and written over.

Erasingusually done in medieval period when good writing material was scarce.

Parchmentwas only real choice for erasure as it was durable to start with and could beerased easily.

Codex C(Ephraemi Rescriptus) is an example of this. About 5/8 of NT was erased (probably the binding had fallenapart first so this was 'scrap') and used for sermons of Ephraem the Syrian.

Sometimes(as with codex C) possible to read the underlying text in the parchmentwith infra‑red photography.

4) Handwriting Styles.

a) Uncial.

FromLatin Uncialus ="inch high" (some exaggeration).

Lookslike a simplified form of the capital letters used for engraving on stone monuments.

Unlikeengraving, no serifs or variations in line thickness.

Similarto modern Greek printed capital letters.

TheUncial Alphabet: see cover page of these notes

Differencesfrom modern printed capitals:

Noteepsilon, xi, sigma

Notedevelopment of omega: two o'smerged

Thiswas the common script from before the time of Christ to the 10th century AD.

Butit takes up a lot of space.

Wordswere run together, perhaps to save space.

Didput a space between clauses and sentences like we would use commas or periods.

Beingrun together was not too bad since ancients typically read the text aloudinstead of silently when reading to self. (Augustine was surprised that Ambrosedid not read out loud when he studied.)

Acursive handwriting style was used for personal or informal notes, but notfor making books.

b) Miniscules.

Inthe 9th century, the informal cursive script was modified to be more readableand was used in 10-15th cens. in making books.

Advantages:

Fasterto write => cheaper.

Morewords per page => cheaper.

Minisculesbrought the price of books down considerably so they became much morecommon.

Asa result, 90% of the extant Greek manuscripts are in the miniscule style.

Theminiscule alphabet: (note more variety)

![]()

Differencesfrom modern printed small letters:

Notebeta (sometimes closer to modern beta), zeta, mu, nu, xi, pi especially.

5)Abbreviations. Several types occurin NT manuscripts.

a)Contraction.

Contractionin English: cannot => can't; Iam => I'm.

Commonlymarked with the apostrophe.

Contractioncommon in Greek NT, especially with sacred names.

Called'Nomina Sacra' = sacred names ‑ Letters were dropped out of the middleand the contraction marked with a bar above the letters.

Didnot save that much space; apparently used to mark sacredness, somewhat likeHebrew tetragrammaton.

TwoLetter Contractions: NOTE the case dependence:

Nom. Sing. Acc.Dat.Gen.

__ __ __ __

ΘC = θεoς ΘN Θω ΘY

__ |

KC= κυριoς \ Note uncial does not

__ useiota subscript

YC= υÊoς

__

IC= zIησoυς

__

XC= Χριστoς

Three Letter:

___ ___

ΠNA= πvευμα CHP= σωτηρ

___ ___

CTC= σταυρoς ΔAΔ= Δαυιδ

___ ___

MHP= μητηρ IHΛ= zIσραηλ

___

ΠHP= πατηρ

LongerForms:

_____

ANOC= •vθρωπoς

______

OYNOC= oÛραvoς

_____

IΛHM= {Iερυσαλημ

b) Suspension.

InEnglish, we will sometimes only write out the first few letters of a word for an abbreviation.

Greeksuspension is somewhat similar, yet not exactly the same.

Ifthere was not enough room at the end of a line and the writer did not want tocarry over a letter or two, he put a line out past the right margin whichmeant, "You supply the ending which the context requires here."

|__

ΔOYΛO|

|margin

c) Ligature.

Ligatureis two letters drawn together to form one letter.

Ligatureused to be rather common in English printing when type was hand set.

ae => æ oe => œ fi => fi

InGreek, rare in Uncial, more common in miniscules.

Examplesfrom miniscules:

![]()

Theoυ form is also found in some uncial script.

Wasapparently done for convenience and faster writing.

d) Symbol.

Symbolsare arbitrary figures/designs used to represent a word.

InEnglish:

$ => dollar ; , => pound ; 4 => cent ;

% => percent, math signs.

SomeEnglish symbols appear to be former ligatures:

&=> et [and] in Latin. 4 prob ct ligature

![]()

Inminiscules:

b. Types of Errors found in NTManuscripts.

1) Accidentalvariants (unintentional).

The vast majority of errors found in aparticular manuscript appear to be totally unintentional, rather like typos interm papers, etc. We attempt toclassify these on the basis of how they appear to have arisen: (1) errors ofsight or writing; (2) errors of hearing; (3) errors of memory; (4) errors ofjudgment.

a) Errors ofsight or writing.

Severalpossibilities here: Scribe saw right, but wrote wrong. Scribe wrote what he thought hesaw. Previous scribe's workwas sloppy or smudged.

(1)Wrong word division.

Uncials did not divide their words, butminiscules do. Thus every scribe who makes a minisculecopy from an uncial must make thousands of decisions on where to divide theletters to form the words. Someexamples:

Mark10:40 (noted in UBS and Nestle)

AΛΛOICHTOMIMACTAIin uncial

Dowe divide as

•λλoις or •λλzoÍς

"for others" "but forthose"

1 Timothy 3:16 (Not in UBS, in Nestle)

OMOΛOΓOYMENΩCMEΓAin uncial

Òμoλoγoυμεvñς μεγα Òμoλoγoυμεvωςμεγα

"we confess how great" or: "confessedly great"

(adverbialparticiple)

(2)Confusion of letters.

Someletters were very similar, though not the same ones in uncial or miniscule.

Uncial:

![]() Problemswith bottom line.

Problemswith bottom line.

Papyrusgrain is horizontal

(=)on preferred side. Ink

canrun/smear along grain.

Ifwriting fast, can get an

intermediateslant line.

Combinations are ambiguous,

whetherone letter or two.

Miniscule:

![]()

(3)Homoioteleuton and Homoioarchton. (similar endings and similar beginnings)

Errors occur because similarity of endingor beginning of two words in a passage results in the copyist looking back atthe wrong place; hence a section (either a word, sentence, or letters) is omittedin the copy. On rare occasions, asection is repeated! Someexamples:

1John 2:23 A number ofmanuscripts skip the section between the two occurrences of "he who hasthe father".

Matthew5:19‑20 τωvoυραvωv occurs 3 times and the sections in between areoccasionally missed.

(4)Haplography or Dittography.

H= writing something once when it really occurred twice.

D= writing something twice when it really occurred once.

1Thess. 2:7

EΓENHΘHMENHΠIOIor EΓENHΘHMENNHΠIOI

εγεvηθημεvηπιoι or vηπιoι

Wasthe v added or dropped? Does itmean: "we became gentle" or "we became infants"?

Thiscould be an error of hearing also; it is not always possible to specify theexact mechanism of error.

(5)Metathesis.

Accidentalinterchange of lettersor words.

Wordorder shifts can happen extremely easily since it often makes little differencein Greek.

Letterorder changes are more serious. Commonly see:

Mark14:65 ελαβovor εβαλov "take" or "put"

Acts13:23 is perhaps partially metathesis and partially a word-division problem:

'salvation' σωτηριαv

'SaviorJesus' σωτηρα Iησoυv

Probablya mixup in the abbreviations:

and

(6)Illegibility.

Sometimesthe text (due to damage) was just plain hard to read. Any type of error can happen.

b) Errors ofHearing.

There is good evidence that sometimes onescribe would read the text aloud from the exemplar (master copy) while otherscribes would make multiple copies. Perhaps this was done when a number of copies were neededquickly. This will produce adifferent type of error than those when the scribe has both his exemplar andthe copy he is making in front of him where he can read both.

(1)Itacism

Whenthe text was read aloud the copyist might not spell it right because he couldnot always tell from the pronunciation how to spell the word.

Particularproblems in Greek are vowels, dipthongs (plus iota-subscripted vowels, notshown) which are pronounced the same:

"eh"=> αι ε

"oh"=> o ω

"ee"=> ι υ η ει oι υι

UBSand Nestle do not normally indicate this sort; it is usually a trivialerror. Some more serious examples:

Distinctionsbetween indicative and subjunctive can be tricky, cf. Romans 5:1

εχoμεv or εχωμεv

ºμειςand ßμεις sounded thesame.

See 1 John 1:4

Oftenboth possibilities make sense. Usually they do not make much difference.

Manyspelling variations do not imply a difference in understanding, as spellings were not standardizedin Hellenistic Greek (no Dictionaries).

(2)Inaudibility.

Thereader mispronounces, someone coughs, etc. Hard to categorize.

c) Errors ofMemory.

Probably no copyist ever copied entirelyfrom memory, but they would constantly look back and forth from the original tothe copy; not every letter, but every few words (contrast good typists, who cancontinually look at the original). Errors occurred in these 'few word' batches of memorization.

(1)Synonym.

Notan intentional change in the meaning, but a synonym of the original word might accidentally be substituted.

Matthew20:34 oμματωv ‑A rare word for 'eyes'.

oφθαλμωv ‑ The common word, so this

is probably the substitute.

(2)Word order.

Easyto change the order and it does not make much difference in Greek. Same result as for metathesis ofwords, but different cause.

Matthew7:17 'do good things'

πoιεικαλoυς or καλoυς πoιει

(3)Influence of a Parallel Passage.

This is normally attributed tointentional harmonization, but it could also be an error of memory. Sometimes the wording from one gospelmight slip into the other when it is copied.

d) Errors ofJudgment.

Occurs more often if you do not have agood original to work with, so you have to decide what was meant. Similar to problem of illegibility, butmay involve other problems as well.

(1)Overlooking an Abbreviation.

Thecopyist misses the line over the word, or the previous copyist left it off.

Example:1 Timothy 3:16 is probably a confusion of letters, plus overlooking an abbreviation.

θεoςor Òς -‑> "God/He who wasmanifested..."

(2)Including a Marginal Note.

Corrector at a scriptorum would sometimesgo through a copy marking places where errors had been made. This is true today when preparing abook for a new edition: See copy ofBerkeley version of Bible in BTS library wih editor Frank Gaebelein's notes forrevision.

Beforeprinting, was hard to tell why marginal notes put in. Was it the proofreader at the scriptorium correcting a realmistake? Or was it a commentby a reader?

Copyistmay mistakenly assume that the manuscript note is a valid correction of themanuscript, so he now puts it into text.

John5:3‑4 Angel troubling the water of the pool. Western and Alexandriantexts omit this. Was it a notemade by a person who traveled to Palestine and asked for public opinion ofthe natives of Jerusalem as to why people were waiting for troubling ofwater at this pool?

(3)Excluding a Marginal Correction.

Avalid marginal correction of the text is left out by the later copyist whothinks that it is only a personal note or who disagrees with judgmentof corrector.

(4)More Familiar Word Substituted for a Similar-Looking One.

Thecopyist thinks the word was mis‑spelled but it was not; it was just arare unfamiliar word.

Luke6:42 καρπoς (fruit) for καρφoς(speck).

Thisexample could be due to a error of hearing instead.

2) IntentionalVariants.

Rarecompared with unintentional as best we can tell (i.e., from study of types oferrors in a particular ms). Butharder to repair because both variants will make sense.

Fromantiquity we know that there were men who tried to make changes in the texts inorder to teach their own doctrines.

Gnostics: Marcion threw out many NT books whichhe did not like (were too Jewish) and he made some changes in the ones hekept. We have no manuscripts whichare known to show this influence. The orthodox would not knowingly copygnostic stuff. When the gnosticsdied out, no one was interested in copying their modified texts.

Hereticsin general have not found it profitable to change the Bible, as the reallyimportant doctrines can not bemodified easily (due to diffuse, repetitive mode of teaching). Heretics typically find it easier to maketheir own Scriptures. Contrast JWswith Mormons.

Thevariants that we have today show little that could be reasonably construed asevidence of heretical corruption.

Mostintentional changes seem to be attempts to "repair" the text onthe theory that it had been miscopied.

a)Grammatical and linguistic changes.

AsChristianity spread into wealthier circles, there arose concern over theBible's non-classical style. (However, God wrote to communicate tothe people of the Koine period). Thus a tendency to classicize the text. Examples:

Changesin grammar: In Classical Gk, 3rdpl aorist ending was always µλθov (same as imperfect). As this was ambiguous (same as 1stsing), Koine writers often used the 1st Aorist ending to have µλθαvfor the 3rd pl. The classicistschanged this α back to an o. The α is typically older, hence theoriginal.

Changesin syntax: The copyist sometimesmisunderstood the syntax so he modified it. In Romans 3:29 we find the variants:

μovov / μovoς / μovωv

Thecopyists apparently thought they were correcting previous copyingerrors, i.e., "Some guy copied this wrong!" In reality they did not understandthe original syntax.

b)Liturgical.

Thetext was modified for use in the liturgy. As in lectionaries, the modifications make the contextclearer. e.g., "And hesaid" ‑‑> "And Jesus said".

Thismay also explain why the Lord's Prayer in Matthew 6:13 has added a doxology(from OT material) to an otherwise abrupt ending. People eventually put into theircopies what they knew from the liturgy.

c)Elimination of Apparent Discrepancies.

Seenespecially in later manuscripts. Example:

Mark1:2 Is it "The prophets"or "Isaiah the prophet"? Since both Isaiah and Malachi are quoted here, some person probablythought this should say "the prophets."

Butthe original style apparently was to cite the major prophet in a multi‑passagequotation (all the minor prophets were on one scroll).

d)Harmonization of Parallel Passages.

Luke11:2‑4 Lord's Prayer in Lukefilled out from Matthew. Ingeneral, Matthew was more popular (as seen from relative number of mss, etc.). Its wording later begins showing up inLuke and Mark.

e)Conflation (combination of variants).

Thisproblem arises when the scribe has two or more variants, usually one in thetext and another in a marginal or interlinear note. He has several choices:

(1)Throw away the marginal note. Danger: If it is a validcorrection from the proofreader, you lose true text from ms.

(2)Throw out the text and substitute the margin. Danger: Marginal note was invalid correction or only someone's comment; alsolose the original text.

(3)Leave it in the margin. Notsatisfactory. Want ms to lookgood when finished, and not confuse the next copyist.

(4)Put both into the text (conflation). Do not lose anything, so the safest, most common practice. Danger: it does introduce a new,combination reading.

f)Attempted Corrections.

Achange has occurred which appears to be more than just a grammatical orlinguistic correction. Examples:

Romans8:2 σε (you) ‑‑> με (me)

Rev1:5 λυσαvτι (loosed) ‑‑>λoυσαvτι (washed)

Latterexample might well be itacism instead.

g)Doctrinal Changes.

Noneed to be toward 'orthodoxy', but in actuality these do tend toward'orthodoxy' (if we define 'orthodoxy' as whatever was commonly accepted inchurch at that time).

Reasonfor this: Christians have gottentheir Scriptures from orthodox Christians, not from heretics. Examples:

1John 5:7-8 The Trinitarian verse:

"Thereare three that bear witness in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the HolySpirit, and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness on earth..."

Occursin only 3‑4 out of 100's of Greek manuscripts. This passage was not used in theTrinitarian controversies of the fourth century, implying it was not in theGreek text. Possibly in Latin textat time.

Mark9:29 "... prayer 'andfasting'."

Fastingbecame a major part of monastic piety, which became popular in the churchonly after about 300 AD.

Textcriticism C whether done on biblical texts or otherChristian authors or any other texts from before the age of printing Cseeks to detect these sorts of copying errors and, if possible, restore thetext to the form it originally had when it came from the author.

c. Transmission of the Text by Hand.

We turn now to consider what we knowabout the specific history of the NT text, beginning with the autographs andcoming down to the time when the NT began to be copied by mechanical printingprocesses shortly after 1500 AD.

This period subdivides into two: (1) aperiod during which the Xn church is illegal, and is subject to sporadic persecution(during which time the text of the mss is characterized by growingdivergence), and (2) the following period in which Xy is legal and (at leastnominally) widely accepted (during which time the mss tend to converge intext).

1) Period ofPersecution (divergence of manuscripts).

The church was considered illegal fromc65 to c325 AD in the Roman Empire. In God's providence, this persecution ended before the collapse ofthe empire in the West. Otherwise(humanly speaking), the NT text might have been far more divergent than it is.

Therewere two main influences in this period, a) tradition & b) persecution.

a)Influence of Oral Tradition.

Some apostles were still alive until c100AD, and others who had seen and heard Jesus for some years more. People who had heard the apostles speakwere prob around beyond 150 AD (e.g., Polycarp, etc.).

Thus there was a source independent ofthe written Gospels for what Jesus and the apostles did and taught; e.g., see Papias'remarks in his Exposition of the Oracles of the Lord.

Such extra information might occasionallybe written in the margin of a ms as a note, and later get into the text.

These oral traditions were circulatinguntil c150 AD, and whatever got written down for long afterward. After this, oral traditions were nottrusted.

TheWestern family of mss seems most influenced by this.

b)Influence of Persecution.

Roman persecution was not continuous, butcould break out at any time so long as Xy was illegal in Empire.

(1)In a persecution, the best copies were those most likely to be destroyed,i.e., those belonging to a large, notable congregation or a major leader. Church leaders and meeting places weremost sought; these would also tend to have the most official copies ofScripture.

SinceChristianity was illegal, it was hard to travel openly, hard to have openmeetings (during persecution). There were no large councils of church leaders (as far as we know)between Jerusalem Council (AD 50) and Nicea (AD 325).

Therefore:

(2)It was hard to compare manuscripts from across the Empire.

(3)Manuscripts were often copied by amateurs without proper checking, since it wasdangerous to take them to professionals.

c)Results for this period:

(1)Most of the variants we have appear in this period, especially in the firsthalf (before c200 AD). Some ofthese variants are hard to resolve since they occur in the earliestmanuscripts which we have.

(2)Manuscripts continue to diverge, so that "Local texts"arise:

Local Text [Versions based on texts] RegionInvolved

Alexandrian [Coptic, Nubian, Ethiopic] Alexandria andsouthward into Egypt

Caesarean [Georgian,Armenian] Caesarea;versions northward into S. Russia

Byzantine [Gothic,Peshitta] Antioch,then Constantinople, spreads from there

Western [OldLatin, Old Syriac] Nowthought to have origin in East

Westernshows up first in N. Africa, then Europe. However, we now have evidence it started in the East, and was spread to the West bymissionaries.

Locations(above) are derived from where the church fathers who quoted these readingswere located, and regions where languages of versions spoken. Locations cannot be derived directlyfrom mss since early mss don't give such information.

2) Period ofAcceptance (convergence of manuscripts).

After c325 AD, Christianity is no longerillegal in Roman Empire. Thisperiod continues in Europe until c1500 AD (when printing takes over), althoughthe rise of Islam in the East complicates things.

a)Influence of the End of Persecution.

Around310‑325 (depending on the area) the church could once again operateopenly as before 65 (although Xy doesn't become the state religion untilabout 400).

(1)Now Xns can use professional scribes. The amount of new error drops off substantially (cp. difference betweenamateur and professional secretary). It thus becomes worthwhile to study variants and try to correcttexts, since errors will no longer be cropping up as fast as corrected.

(2)Can now openly travel and compare texts. Xn leaders quickly see the need for standardization of the text andbegin to do so. However, mostpeople (and leaders) prefer their own local versions. (Sound familiar?)

b)Influence of Changes in the Greek-Speaking World.

100to 200 AD had been the great golden age of the Roman Empire, with good rulers,peace, economic prosperity. After 200 AD, the Roman Empire weakens, with economic decline, badagricultural practices, growing welfare state, education weakening.

Inareas where Greek not native language, it begins to recede (esp. in ruralareas) in favor of local languages: Coptic, Syriac, Armenian.

Latinalso loses as Barbarians come into West after 250 AD.

Therise of Islam in the 600's causes a major change in language and muchmore. Arabic becomes the languageof culture and commerce in Palestine, Egypt, N. Africa, Spain.

ThusGreek usage shrinks back with Byzantine Empire to Asia Minor and Greece,plus a few isolated patches elsewhere. This is the area where the Byzantine text was local version.

ThusByzantine text becomes dominant, since Byzantine Empire survives Arabconquests and Greek is still spoken there. Alexandria, Caesarea, etc. fall to Islam and Greek usageends there.

c)Results from this later period:

(1)Few furthervariants occur other than ones which result from standardization (conflation,smoothing, etc.).

(2)Various mss families tend to grow more like each other as marginal notes fromcomparison are incorporated into the text.

(3)Constantinople becomes the center of the Greek-speaking church (Rome of Latin-speaking), soits text becomes dominant as other areas are taken over. During the 4th‑8thcenturies the percentage of mss which are Byzantine greatly increase,from virtually none in 4th cen to dominance in 8th cen.

Hence95% of our extant miniscules are Byzantine, as Byzantine family was dominantwhen they were first made. Findmainly Byzantine corrections in the other text families.

2. History of the Text since Printing.

With the importation of printing into theWest and its technological development into a massive industry, 1000sof copies of a text can be printed which are textually identical. It is still possible to make copyingerrors (and some are whoppers!), but since every copy will no longer be uniqueit is far more feasible economically to check a text carefully before it goesto the printer.

a. The Rise of Textual Criticism (16th‑20thcenturies).

The enormous reduction of textual copyingerror printing makes possible leads to systematic attempts to find and restorethe best possible text of ancient documents, of which the most widely printedwill be the Bible. We will dividethis period of the history of the text since printing into three periods: (1)the Textus Receptus becomes dominant (16-17th cen); (2) textual studyprogresses (18th); (3) the abandonment of the TR (19th-20th).

1) The TextusReceptus Becomes Dominant (16th‑17th cens.).

a)The Printed Greek New Testament.

Printing existed in China & Japan by800 AD, but only reaches the west in the late 1300's. Movable metal type and the printing press were developedto make it practical about 1450. The first books were printed in Latin, the international language ofscholars in the West.

When Constantinople fell to the Turks in1453, many Greeks fled west as refugees. This brought a great spurt in interest in Greek, which had not been veryaccessible previously as RC and GO churches were enemies.

(1)First Printed Greek NT.

CardinalXimenes in Spain made the first plans for a Greek printed Bible, as part of amultilingual OT-NT. It wasdesigned as a scholarly rather than popular edition. It had the OT in Hebrew, Greek, andLatin, and the NT in Greek and Latin.

Cameto be called the "Complutensian Polyglot" after the Latin nameof the city in Spain where published (Alcala = Complutum).

Thiswas the first Greek NT ever printed (1514), but it was not published (distributed)until 1522 because papal beauracracy held it up (had to have permission topublish Bibles).

(2)First Published Greek NT.

WhileXimenes was working on this, a printer in Basle named Froben found out anddecided to publish a much cheaper Greek edition of the NT before Ximenes.

Frobengot help from Erasmus, the best Greek scholar in Europe at the time. But Froben forced him to work fast, soErasmus could only use locally available manuscripts.

Erasmus'Gk ms of Revelation lacked the last page, so Erasmus translated the LatinVulgate back into Greek for this part.

Editionwas printed and published in 1516 (dedicated to the Pope, so permission topublish came quickly).

Sinceit was smaller and cheaper than Complutensian Polyglot it had a much largercirculation.

TheFroben text is basically Byzantine.

LaterGreek NT's for several centuries follow Erasmus's text (rather thanPolyglot or Greek manuscripts) even though it has wordings which are not usedin any Greek manuscript.

e.g.,the last 6 verses of Revelation continue to follow Erasmus rather thanGreek. "Book of life" inLatin and TR (and KJV) should be "tree of life" acc to Gk. manuscripts.

Yetboth the Polyglot and Erasmus' text were based on relatively few manuscripts(those which were easily accessible).

(3)Later Printed Editions of 1500s.

Thesealso depended on a few late manuscripts as there was no textual criticism yet.

Thetendency was to use Erasmus' version (occasionally corrected against amanuscript) rather than to print a text of the Comp Polyglot or somemanuscript.

Nocopyright laws yet, so easy to do. Over the next century, only Froben'stypographical errors are changed in the various printed Gk texts.

b) The "Textus Receptus."

Theterm "Textus Receptus" is used in three distinct (but somewhatoverlapping) senses:

(1)Narrowest sense: Elzevir brothers'2nd edition of Greek NT (1633). Comment in the preface, "this is the text received by all." From this was coined the phrase, "TextusReceptus." So refers to thisedition.

(2)Broader sense: All early printededitions of Gk NT, i.e., the printing up of the sort of text which we find inthe miniscules, especially those copied in the last centuries before the timeof printing, which is basically a late form of the Byzantine family as it haddeveloped by the 15th century.

(3)Broadest sense: The form of thetext of any work written before printing as it was transmitted to thetime printing begins. Applies toall ancient literature (the "TR" of Homer, etc.)

TheKJV does not follow the "TR" in the narrowest sense, but does in theother two senses.

c)Beginning of Textual Studies.

Witha fairly fixed printed ed. of the Greek NT, much more elaborate textual studycan be done than anyone in antiquity (Origen, Jerome, etc.) everattempted. We discuss some of thisunder the headings (1) the publication of critical apparatuses, (2) theuse of uncial mss, and (3) the collection of variant readings.

(1)Publication of Critical Apparatuses.

Withthe coming of printed editions, it was much easier to compare mss (and so begintextual studies) because there are many identical copies of one"standard" text (even tho itself somewhat variant) to compare msswith. Comparing actual mss withouta standard is much harder as one worker can't tell what another is doing.But now deviations can be compared with a common printed edition.

Stephanus’(Latin name of Robert Estienne) edition of 1550 includes textual apparatus (hadenough mss to do this) listing variant readings. KJV is translated from this (and a Beza edition).

Fromthis time on, some editions will give critical apparatus and some willnot.

Stephanused. of 1551 was first to have verse divisions.

(2)The Use of Uncial Manuscripts.

(a)Theodore Beza, successor to Calvin at Geneva. All early editions were based on miniscules, butBeza had two uncial mss which are still important today: codex D (Bezae) and codex D2or Dp (Claromontanus), the two major Greek representatives of theWestern family. Though Beza made10 eds. of Gk NT in his life, didn't use these uncials much. Their textdiverges greatly from the miniscules and he did not know how to handlethis.

(b)Brian Walton. Published a Polyglotin 1657, still used today because it contains Ethiopic, Syriac, Persianversions which have not been much worked on. Walton used uncial CodexAlexandrinus as one source for his Greek NT in the Polyglot. Alex. is our earliestBzyantine text in the gospels (the rest of it is Alex.), so it did not look sodivergent from TR.

(3)The Collection of Variants.

Begantrying to find as many variant readings as possible. This work is not completely done yet.It is hard to find all variants in hand‑written manuscripts (and thereare 1000's of manuscripts!). Hasbeen done carefully for all uncials, many miniscules, a few lectionaries.

(a)Brian Walton was the first to do systematic work. Compared manuscripts in differentlibraries.

(b)John Fell's Greek NT (1675 ed). Lists variants from over 100 mss and someversions. The first printed ed. to cite Codex Vaticanus (B). Does not always tell reader which manuscriptsupports which reading. Does tellyou what he looked at and what the variants are.

RCCwas not happy about Protestants using Vaticanus, so not available toscholars until the mid‑19th cen. Somehow Fell got to use it.

2) Textual Study Progresses (18thcentury)

a)Continued Dominance of TR. Thiswas the normal printed text, with some minor exceptions.

b)Collection of variants continues, as does location and survey of newmanuscripts.

JohnMill's Greek NT (1707) contains 30,000 variant readings (cp UBS c5,000).But the text he prints only varies from the TR in 210 places.

c)Development of Critical Principles.

Withthe collection of all these variants, the question naturally arises: How do youdecide which variant is more likely than its competitors to be original? Some attempts in this century to develop"rules" for making decisions.

(1)John Albert Bengel [conservative; commentary Gnomon NT]. In Prologue to 1734 ed. of Greek NT,states two principles: